Reserve Policeman George Booker Mogle was killed in the line of duty in 1946. He was shot by a prowler suspect on July 31 and died of his wounds a week later, on August 7. For more than 50 years, this was the only information generally known about Mogle. The story faded into history. He was considered the first LAPD reserve officer to be killed in the line of duty, but there were no further details and not even a picture of him was thought to have existed. Eventually, even his full name got somewhat lost, as he became known as G.B. Mogle. And G.B. Mogle was nowhere to be found on the memorial of LAPD officers killed in the line of duty.

We know now that Mogle, and what happened to him, did not entirely disappear. The information was out there, just waiting to be rediscovered. There were newspaper clippings and, finally, a few pictures, revealing who he was. There were family members, some by now far removed, who had steadfastly kept those tattered, yellowed newspaper clippings and photographs. And we now know that a few generations followed this hero into full-time careers with the LAPD. Mogle’s son, George Ervin, joined the LAPD as a full-time officer in 1947, just a year after his father’s death. He retired as a sergeant of police in 1967, but he would still be made to “stand by to stand by” for an additional 30 years before his father’s name would be added to the roll call of fallen heroes in 1996.

And it was not until last year, 2011, that a further effort was made to find out who this hero was. The first steps occurred as a result of inquiries for the new reserve officer exhibit being planned at the Los Angeles Police Museum, located in the old Highland Park station. Lieutenant Craig Herron tasked his team to find some information about Policeman Mogle. A picture was found. It had been hanging on a wall at 77th Division where Mogle had been assigned and worked his final shift. The Rotator began to look for information in preparation for this article. Newspaper archives were researched and family members were located. And, as The Rotator went to press, a surprising discovery was made, providing a final, ironic twist to the story.

This is what we now know about Reserve Policeman George Booker Mogle and what happened that fateful summer in Los Angeles in 1946.

George Booker Mogle was born in Kansas at the turn of the century on August 31, 1900, to William Arley and Daisy May Mogle. His grandfather, Andrew Jackson Mogle, had come to Kansas to stake out homestead land and make a life for his family. The young George Booker was named after his uncle, George Booker Mogle, who had died tragically only a few years before in 1896 after falling off a spooked horse crossing a river and being mortally kicked in the head by the horse.

A World War I draft registration card dated September 1918 lists the then-18-year-old Mogle’s occupation as “repairman” employed at the Liberty Auto Company in Wichita. Records say that his mother Daisy died a year later in 1919. By 1921 he was in Los Angeles, having married Ida Viola Duncan. He and his new wife lived on 65th Street in Los Angeles. They had two children, George Ervin and Luella.

His daughter, Luella, now 87, remembers her father was “big-hearted but somewhat stubborn.” When, at 18 years old, she had fallen in love with the boy next door and decided to marry him, her father was dead set against the idea — not because he was against the young man, but because America was at war, and Luella’s fiancé was headed into it. But his daughter was equally stubborn and in August 1943, George Booker was there, of course, to walk her down the aisle to marry Private First Class William Tralle. Later, William would also become an LAPD officer, retiring as a sergeant.

George Booker Mogle continued to work as an auto mechanic, usually working out of his house. His brother, Clifford, was the personal bodyguard and chauffeur for actress Janet Gaynor (1937’s “A Star is Born”), and he would often come by the Mogle house in his uniform, driving his limousine. When World War II hit, Mr. and Mrs. Mogle answered the call for service. Ida Viola would work at McDonald Douglas. And George Booker became a “reserve” Los Angeles policeman.

Wartime Los Angeles was a boom town, with the area generating about 17 percent of the total American war production. At night, the city was blacked out. Luella remembers those worrisome times, as families placed blackout curtains on their windows to darken the city, and searchlights scanned the skies for enemy aircraft.

The 1940s was also a period of change for the LAPD as the Department transitioned in stops and starts from the “turbulent 1930s” of graft and corruption to the gradual reform beginning in the 1940s. As the United States entered World War II, the LAPD found itself back to the manpower levels of 1925 as its officers went off to fight in the war. To supplement the force, the LAPD turned to “auxiliary” police officers. The LAPD Reserve Corps would not be officially established by the City Council until 1947, but these auxiliary officers had already found themselves providing vitally needed police services, including patrol. At one point in the 1940s, the auxiliaries swelled to 2,500 officers.

It was during this time that Mogle was assigned to 77th Division. He was in charge of what was called “Company 2.” Mogle and his partner Fred Sturdy were working patrol in the dark morning hours of July 31, 1946, a Wednesday. Records show the summer temperature had dipped to 60 degrees Fahrenheit. They observed and stopped a suspicious pedestrian on 60th Street, between Vermont and Kansas Avenue, to question him. The suspect had been darting in between and through the houses. What happened next was described by Mogle himself at the hospital, before he died, and quoted by the newspapers of the day.

“We’re police officers, what are you doing here?” Mogle inquired.

“What’s it to you,” the “squinty-eyed” suspect replied.

The suspect then pulled out a gun — “an old-style 32 revolver with a well-worn barrel” — and fired point blank at Mogle, hitting the officer in the stomach. The suspect then ran off as the officers returned fire.

Mogle was transported to the Georgia Street Receiving Hospital, where he underwent surgery. The Rotator asked Luella if she remembers where she was when she heard the tragic news. “It was so long ago,” she said, “But I think police officers came to our house, and we headed to the hospital.” There is an old newspaper clipping with a picture of the reserve policeman in a hospital bed with his distraught wife and daughter by his side. Luella said her father was unconscious much of the time. The doctors had been unable to extract the bullet, which had been lodged in the lungs. As we know, Policeman Mogle did not survive. He succumbed to his wounds a week later, on August 7, 1946.

The LAPD used to keep a scrapbook of newspaper clippings from 1945 until Chief William H. Parker passed away in 1966. There is an article saved from the Angeles Mesa News, “Police Reserves Pay Tribute to First Member Killed on Duty.” He had been shot, the article said, “while attempting to arrest a suspect in the 1100 block on West 60th Street.” The suspect, then still at large, was described as a Caucasian male, 35-40 years old, 5-feet, 9-inches tall, weighing 150 pounds and of slender build and fair complexion with brown hair and a thin face.

The article reported: “Uniformed police Reserve Corps members from the 12 police divisions of the city attended (the) memorial service for Booker Mogle. Chief of Police C.B. Horrall presented Mogle’s badge to his family.”

Detectives apprehended and arrested a suspect: a 38-year-old laborer named Clifford V. Christianson. The arrest was said to have been the result of an “underworld tip” and the description of the suspect was, they said, a match. However, the suspect was never charged with the shooting. Family members say that the officer’s son was forever disappointed by these circumstances. No further information was found as to why it ended up the way that it did.

After that, the story slowly faded away. George Booker’s son, George Ervin, who had served in World War II and been a prisoner of war (having been shot down over Germany and before being liberated by the British), was serving in the occupation of Japan at the time his father was killed. He came home and joined the LAPD full time in 1947 and served for 20 years. We know that, during his career, he shot and killed a burglary suspect, and he appears in several other news stories during the 1950s.

Why the story of G.B. Mogle got lost, as it did, is difficult to say for certain. The circumstances are probably due to the somewhat undefined status of reserve (or then “auxiliary”) officers in the Los Angeles Police Department in those days, one year before the official Police Reserve Corps would be established. And the Department was still in the birth pangs of reform. The reform-minded chief Arthur C. Hohmann would lose his job in 1941 after only two years and be replaced by Clemence B. Horall, who would find himself embroiled in a scandal eight years later. Six months after Mogle’s murder, the city would be shocked and engrossed by the “Black Dahlia” case. So Policeman Mogle would be laid to rest and would have to wait. After the Reserve Corps was officially created, reserve officers were relegated primarily to special event enforcement, including traffic and crowd control, which would last until the program was revamped in the 1960s with an emphasis on line officers for patrol. By then, it had been forgotten that a previous generation had already paved the way, providing such services when the country was at war. Coincidentally, Mogle’s son retired in 1967, just one year before the first line reserve Academy class began.

It is, perhaps, an example of fate that, when The Rotator called the phone number we had located for the widow of George Ervin, the man who answered was also a retired LAPD officer and turned out to be the son-in-law of Sergeant Mogle. Kenneth Coleman just happened to be there, having driven 1,000 miles from California to take care of his mother-in-law, Mrs. Ruth Mogle.

Sergeant Mogle was a humble man, part of the “Greatest Generation,” as they say, and family members say he was hesitant to talk about the war or the sacrifices endured. And he kept mostly quiet to the slight his father had endured. But some people were listening. In the mid-1990s, Leonard Munoz, a Director of the Los Angeles Police Protective League, and others heard the story and pushed for the recognition of George Booker Mogle. A 1995 article in the newsletter of the Los Angeles Police Historical Society reports that they were contacted by a retired detective, who told them about the forgotten hero. Finally, on July 31,1996 — 50 years to the day he was shot — George Booker Mogle was finally honored in a ceremony at Parker Center, and his name was added to the Police Memorial, “from which it had been inadvertently omitted.” George Ervin and Luella, the son and daughter, were in attendance. The son, having flown down from Oregon, where he had since retired, said: “I feel that, at last, he finally got the honor he deserved.” Newspaper reports at the time said that George Booker’s widow was there, but this was not true; they had misidentified Ruth Mogle, who was actually George Ervin’s wife. Ida Viola had died earlier that year, in March; she did not survive in time to attend the memorial of her husband. Retired Sergeant George E. Mogle subsequently died in 2006.

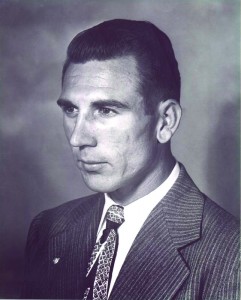

As The Rotator went to press, a surprising discovery was made. We sent a draft of the story to the Mogle family. The draft included the photograph that had been hanging on the wall of 77th Division all these years. But the family said the picture was not George Booker. It was, in fact, a picture of George Ervin, the son. Father and son, in a final ironic twist, had been mixed up, with the father once again facing obscurity. The family provided a rare photo of the real George Booker, revealed here, in these pages.

George Booker Mogle is buried with his wife in the Inglewood Park Cemetery (originally established in 1905, when he was but five years old). Luella thinks she might still have the badge given to the family by Chief Horrall. “But it was so long, long ago.”

Long ago certainly, but — finally — not forgotten. Rest in peace Los Angeles Reserve Policeman George Booker Mogle, EOW August 7, 1946.

(Editor’s Note: In addition to the individuals mentioned in this article, The Rotator would also like to thank the following for helping us to research this story: Reserve Officer and Los Angeles Police Reserve Foundation President Mel Kennedy, Officer Darrell Cooper, Kathryn Tralle Ryan, Leroy McCormack and Jerry and Paul Stewart.)

Captions:

Revealed: a rare photo of George Booker Mogle

A newspaper clipping of the wounded Reserve Policeman Mogle, with his wife and daughter by his side. The officer would succumb to his wounds.

Portrait of George Ervin Mogle. This picture was previously thought to be of George Booker Mogle, and had hung on the wall of 77th Division.